Dean Ball, a fellow at the libertarian Mercatus Center and otherwise classical liberal type wrote a long tweet last week pointing out that Trump critics have not properly engaged with the intellectual foundations upon which Trump’s economic policies are (possibly) based. In particular, that there are positive externalities from a manufacturing sector in the US, and that government intervention is the only way to obtain the benefits of that externality. What particularly caught my eye was when Rohit Krishnan replied with the standard free market keyhole solution; that Trump’s tariffs are too much, and you should tailor your interventions into the market to focus on the smallest possible intervention with subsidies for particular products. That is exactly what I would have suggested. Yet:

https://x.com/deanwball/status/1907641739369943396

Alright, so I’ve been called out as not thinking about the problem at all, point taken, let’s try and engage with the cited people and see what they have to say.

The Intellectual Case

Dean mentions Stephen Miran (Trump’s chair of the Council of Economic Advisors) and Oren Cass. Cass I’m more familiar with, and I find quite unconvincing. While he discusses benefits from manufacturing related to innovation and national security, which we will definitely revisit, he spends a lot of time discussing the fact that loss of manufacturing impacts people via job losses and community. This seems very close to bemoaning dynamism itself. Economies adjust, technology advances, and there are winners and losers. We should not ban light bulbs to make sure candlemakers remain employed, just like banning automation at ports to keep longshoremen jobs is a bad idea. For this reason, I’ll be focusing on Miran since I find his explanation of manufacturing losses far more interesting, and his arguments about national security and innovation far more convincing.

Miran published two white papers last year “Brittle Versus Robust Reindustrialization” in February for the Manhattan Institute and “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” in November for Hudson Bay Capital.

The earlier paper from February is actually somewhat contrary to Dean’s dismissal of targeted tariffs as “whack a mole”. Miran spends the majority of the paper arguing for fairly standard conservative supply side reforms— or what we might these days call “Abundance” policies: regulation slashing, NEPA reform, occupational licensing reform, reducing powers of unions, land use reform, and moving towards a Destination Based Cash Flow Tax instead of a standard corporate tax.

Miran then turns towards the demand side and envisions a more robust defense industrial policy with stronger buy-American provisions. He sees this as both economically and militarily beneficial. Even though he doesn’t specify expanding defense spending, he criticizes current buy-American rules as far too lenient and thus sees a radical shift in production as possible without much change in spending. Miran also discusses expanding these buy-American rules to strategic industries like semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, satellites, etc.

Next up: tariffs. Miran is a fan, particularly in defense supply chains to reduce Amerian trade linkages with China. He also suggests that in some cases, tariffs will be required not just on products with Chinese country of origin, but for all imports of that product if the industry is strategically important, but he doesn’t specify any details here. Nonetheless “Both tariffs and expanded Buy American requirements should be phased in gradually, with credible pre-commitments, to give firms the time and necessary planning horizon for reconfiguring their supply chains.”

Restructuring Global Trade

Miran’s second paper, published in November is far more radical. He says this is not a policy prescription, but a discussion for what the next Trump administration might do. Since he was then appointed chair of CEA, it seems like it may in fact be quite prescriptive.

The foundational point, mostly absent in his previous paper, is that the US dollar’s role as the world reserve currency has an unrelenting upwards impact on the dollar’s value, which disadvantages exports and particularly manufacturing. While in a typical model of international trade, exchange rates will always adjust to balance trade flows (if your country buys more imports, your currency declines, which makes future imports more expensive), the reserve currency role creates a continuous demand for dollars unrelated to trade flows. Thus, as the world economy grows, the demand for dollars continues to expand, which results in a very strong dollar. This is known as the Triffen Dilemma, named after the economist who noted this phenomenon in the 60s. The dilemma makes US exports unattractive and thus harms the manufacturing sector.

Taking increased manufacturing as a given policy goal, Miran explores the policy options available for the Trump administration to reduce the negative impacts of the Triffen Dilemma, the first of which is tariffs.

Miran makes a sophisticated case, including some points about tariffs that I was either unaware of, or had forgotten since my international finance class in college. Particularly that large economies can maximize welfare by having positive tariffs because they can extract price reductions from foreign producers given the country’s large market power. Of course, Miran declines to note that this is only welfare enhancing if you disregard the welfare of non-Americans. Miran also points out that there can be currency adjustments, as there was between the US and China during Trump’s last administration, which meant that American consumers didn’t see price increases as a result of the tariffs because the Chinese yuan lost value. In practice, this means the tariffs were paid for by Chinese citizens broadly who dealt with a less valuable currency and pricier imports. Thus, depending on currency adjustments, tariffs can raise prices or they can adjust the currency values such that the US treasury can effectively tax foreigners.

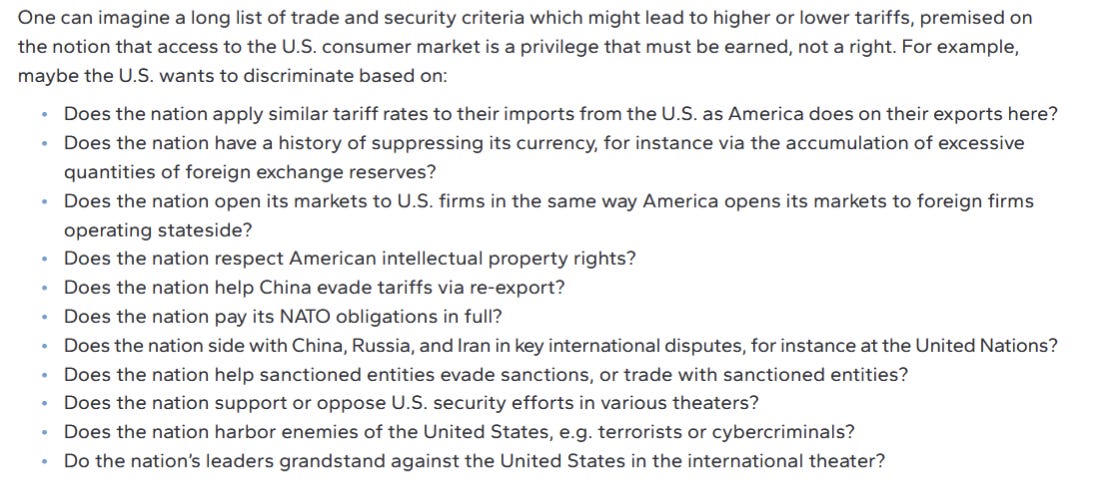

The paper goes into a lot of detail of ideal tariff implementation (gradual) and how these can be used for leverage to help achieve US national security goals:

He also notes the administration needs to be careful with tariff implementation to avoid retaliation, as that would risk the US shooting past any theoretical “welfare enhancing” tariff level or even international trade broadly blowing up broadly.

What was completely absent from this section? Any mention that tariffs could improve the US manufacturing sector.

The Global Currency System

Finally, we arrive at the big guns. The Triffin Dilemma results in an overvalued US dollar, so the government could pursue a policy of direct devaluation. The problem, as Miran notes, is that if you devalue the dollar, people won’t want to hold dollar denominated assets.

Miran then details potential multi-lateral approaches Trump could take to devalue the currency while avoiding a run on US treasuries. He suggests a hypothetical “Mar-a-lago Accord” where the US leverages tariffs to bring allies to the negotiating table. Basically, as long as the US is the security provider to our allies, they should help pay for it via buying treasuries, and in particular “century bonds” to tamp down long term interest rates, and if they don’t, they will lose access to the US consumer market via large tariffs. In his own “Feasibility” section though, Miran admits this approach may be pretty tough to get working. Much of global US dollar foreign currency reserves are not in the hands of traditional allies and they may not be able to be convinced. Moreover “a large fraction of the U.S. debt is held by private sector investors, both institutional and retail. These investors will not be convinced to term out their Treasury holdings as part of some sort of accord. A run by these investors out of USD assets has potential to overwhelm the bid for duration coming from a term out from the foreign official sector.” Sounds dangerous to me.

Miran next turns to unilateral currency approaches. He acknowledges as much, but these are incredibly risky. First, the president can leverage the same law empowering the Treasury’s sanction powers to disincentivize the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves. For example:

…impose a user fee on foreign official holders of Treasury securities, for instance withholding a portion of interest payments on those holdings…Some bondholders may accuse the United States of defaulting on its debt, but the reality is that most governments tax interest income, and the U.S. already taxes domestic holders of UST securities on their interest payments…Of course, a user fee risks inducing volatility…

You betcha some bondholders will complain!

Another unilateral approach is to counteract foreign holders of USD reserves by having the government accumulate foreign currency reserves, thus pulling their currency out of the market, reducing supply, and appreciating their currencies. Miran notes that this introduces the mirror risk of the above; if the administration adds a user fee on Chinese owned US government debt, but simultaneously tries to appreciate the yuan by buying Chinese government debt, the Chinese government will just add a user fee onto the debt owned by the US Treasury, or worse just default on their obligations to block American attempts to appreciate the yuan and harm American taxpayers.

Finally, Miran points out that because these currency approaches are much riskier, tariffs are clearly the first choice before any radical policies are undertaken.

Free Markets Finished?

Having read these papers, I can see Dean’s point quite well. China has established a massive manufacturing juggernaut, while the US has mostly not kept up. And while classical liberals can certainly critique that China could have a much wealthier populace and less political oppression if they didn’t do all this central planning, the risk is still that they’ve done enough to now threaten others with poverty and oppression. Miran isn’t a leftist or a socialist or an idealist. He clearly buys into the fundamental economic reality that markets work and efficiently allocate capital, yet he has spotted a market distortion that places the global world order and American national security at risk. It frustrates my libertarian leanings, but perhaps abandonment of free market principles is required to save the free market system. And yes, we’ll get to the fact that Trump has only pretended to do the reading, but I also understand Dean’s annoyance with people claiming “there is no plan”. Because clearly there is a really detailed one here from Stephen Miran, who seems to be the only person taking geopolitical situation clearly.

But the more I thought about it, the more issues I see in the plan. As a precursor, I want to reemphasize that this plan to reformulate the entire global trade system is extremely ambitious, radical, and risky. My counterpoints and alternatives are not compared to a dull status quo, but a plan that risks our diplomatic ties with our allies, the dollar’s status as the reserve currency, a US debt crisis, and indeed our entire economy. A plan that risky should be certain there are not alternatives or issues. I think there are. First, the elephant in the room we’ve been ignoring.

We’re Not Doing the Plan

Miran is constantly discussing the trade-offs, the risks, and the need for clarity when plotting this new global trading order. If allies are spooked off, if you can’t bring people to the negotiating table, if you upset financial markets, then the plan isn’t going to work. Therefore, Miran argues that what is needed is supply side reforms and simultaneous gradual tariff ramping up. This is a core feature of the plan, not some text copy-pasted onto the end. If we’re trying to get other countries to do something, we have to make it clear what each player’s options are and what the consequences are. He repeats many of these points in his April 7 speech.

Trump didn’t bother with any of that. Hours before the April 2 tariffs were announced, it still wasn’t clear the administration even knew what they were going to do. The announced tariffs are extremely high, inviting retaliation, something else Miran says should be avoided. They are also not separated into buckets based on national security requirements. By not differentiating, many of our former allies are now joining with China in adding retaliatory tariffs. This is a nightmare scenario for the Miran plan.

In Miran’s April 7th speech, a major thing missing is the need for caution and gradual tariffs. Presumably Miran knows the ship has sailed there. Maybe there was a faction struggle inside the White House, and Steve Bessent and Peter Navarro had way more radical plans than even Miran’s very risky one. Or maybe Miran never cared about being cautious. Or perhaps Trump is just a mercantilist and thinks it’s 1700. Regardless, the plan is dead.

And that’s just the points about tariff gradualism and clear negotiating goals. If you were really trying to target manufacturing specifically, you’d need to be actively working to make immigration easier and more streamlined (more workers for US assembly lines). And of course, why would you tariff agricultural goods? We don’t want to push Americans into farming, that would harm manufacturing even more.

Nonetheless, unlike Trump and the whole White House, I did do the reading, so I might as well add some actual critiques of the plan. First, I’d like to attack the fundamental premise.

Do you actually need manufacturing?

Miran spends no time defending this policy goal, as he takes it as given that there is bipartisan interest in this. But I’d like to talk about how necessary this really is. I loved last year’s ACX review of How the War Was Won, and there’s no doubt that US productive capacity won the war for the allies, but are we planning to fight World War 2 again? We have nuclear deterrents now. Can’t you just give Taiwan nukes and avoid the 41 page white paper and the collapse of the US economy altogether? Who cares about made up accords, and Triffen Dilemmas and quasi-legal government debt vehicles if you just say “hey, we made a Pacific version of NATO, don’t cross us on this, Trump is nuts” and then we just keep letting the economic system chug along.

Moreover, it’s worth noting the US fought several wars while still being a manufacturing powerhouse and things didn’t turn out great: Korea and Vietnam are not really on the US military’s career highlight reels. Perhaps it’s possible that having a dominant manufacturing sector is necessary but not sufficient.

Dean Ball does argue from his perspective that manufacturing is less about national security production during a war, but rather about innovation and how AI will soon transform the economy. AI will change everything digitally, but will require manufacturing prowess to leverage those digital advances into the real world. If China owns all the manufacturing capability, then even if US labs get to advanced AI or AGI (artificial general intelligence) first, they won’t be able to capitalize and we will end up being stuck with CCP-value aligned AIs instead. This seems reasonable, but it’s also quite difficult to foresee how important manufacturing output today is related to what happens in a crazy AI futures. Still, let’s keep this in mind.

How important is the reserve currency to national security?

I won’t spend much on this, because I tend to agree with Miran that the national security benefits are good. But it’s not like US government dollar sanctions have really dealt any blow to Chinese ambitions. Russia is having a tough time, but again it’s not clear America is achieving our goals even if the sanctions on Russia are challenging for them. As long as we are considering upending the entire system, I’d like to at least know this isn’t the answer. Strangely, Samuel Hammond points out that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said positive things about putting the US back on a gold standard. In essence this position would aim not just for some rebalancing to avoid the Triffen effects, but actually swing the balance far into the other direction, forcing the economy to become more like China, producing industrial goods and consuming far less. This seems like a bad idea too as we not only give up the national security benefits but also become significantly poorer to appease the desires of some elites.

The Special Case of Canada

Suppose we take the Triffen Dilemma seriously and that we must maintain reserve status while also requiring a manufacturing base for national security purposes. Why are we not leveraging our relationship with Canada to address all three? Canada has their own currency. They aren’t impacted by the Triffen Dilemma. If we put up tariffs or defense quotas around imports to the United States and also Canada, the Canadian dollar would not face headwinds from being a reserve currency, it would just depreciate, sparking a manufacturing boom. What’s more, we (used to) have very low trade barriers with Canada, meaning we could take advantage of the manufacturing there (and lower Canadian dollar) for cheap manufacturing inputs and could easily see spillover effects for some manufacturing within the US taking Canadian outputs and adding high tech value adds. I think this approach would also satisfy Dean’s concerns about AI and manufacturing; if US labs developed AGI and leveraged Canadian manufacturing to build robots, chip fabs, drones, or whatever crazy sci-fi things we are going to cook up, that’s totally fine and would benefit both countries immensely.

The problem with having a manufacturing base in China and low trade barriers is that China is a geopolitical adversary and they have an incentive if tensions get bad to cut us off from their manufacturing base. Taiwan is an ally, but vulnerable to Chinese invasion. There are similar if lesser concerns about South Korea or Japan. Canada, however, is ideally located deep within the American security shield. They are NATO members so we are already treaty bound to protect them, we have an integrated defense in NORAD, and our armed forces undertake joint operations routinely. Canada can be defended almost as if it is US soil. And of course, especially relevant to American conservatives, there are huge cultural overlaps between Canada and the US as well. They are also a liberal democracy, Canadian actors have huge roles in American pop culture, they primarily speak English, and they even participate in our national sports leagues.

Would Canada assent to have large tariff barriers raised against others besides the US, and have their currency depreciate against the dollar? There are costs. For this arrangement to work, there would likely need to be an additional binding treaty to make sure policy agreements between the countries could not be suddenly revoked. This means an explicit loss of flexibility in policy options going forward. However, that’s essentially what NAFTA, NORAD, and NATO are: binding agreements that make everyone better off by restricting everyone’s options. Having unique access to the US market when many other countries are cut off could be quite enticing, and the US could also sweeten the deal with other benefits.

This seems much simpler than any of Miran’s longshot policy prescriptions to reshape the entire global trading order and doesn’t require trying to coerce dozens of nations, instead just working with a single close ally. Of course, Trump has alienated Canada so any agreement would be pretty hopeless at this point, but I think this is an under-discussed error in our foreign policy.

One final point: Canada is pretty small. Its entire population is less than California and its economy is also much smaller than the US, so there may be limitations on how much manufacturing from Asia can be replaced solely by Canada. Mexico is obviously the second best option for this “just put the manufacturing nearby but in a country that doesn’t use the US dollar” plan. They have a much larger population and many manufacturing plants exporting to the US already given their generally lower wages. However their economy is even smaller and their present security arrangement with the US would be totally inadequate. Not to mention the political challenges of Trump trying to suddenly build a relationship with Mexico. At the very least though, this build-in-Canada approach could be one step of several undertaken.

We Tried Nothing and We’re All Out of Ideas

We have no empirical data on the Triffen Dilemma’s magnitude, especially in a floating currency regime. Full Stop. Triffen originally wrote about the reserve currency problem in relation to the Bretton Woods system. Miran is arguing for reconfiguring the entire global economy, risking total economic collapse, but we don’t even know if this is the key insight or how much its contributing to the problem. Miran himself notes that despite the Triffen Dilemma (which forces countries to buy US debt), US government borrowing costs are not particularly low. Miran is mostly puzzled by this and moves on, but it could be quite significant. Especially since a major plank of the plan is to bring trading partners to the table and force them to buy longer term treasuries; they already do this, and apparently it doesn’t accomplish what Miran wants already!

Moreover, the Triffen Dilemma impacts all exports, not just manufacturing. Taking steps to devalue the dollar could improve manufacturing, but it also would just make US services cheaper too. We already have network effects related to services like finance, technology, and healthcare. Why wouldn’t those sectors see surges in growth even larger than manufacturing? Other countries have seen declines in manufacturing as percent of GDP and they do not issue the reserve currency. It seems plausible that Triffin effects could be dominated by other policies.

Miran spends most of the February paper discussing supply side reforms. He mentions them offhandedly in the "User’s Guide”, but we should try these first. And there’s a huge menu to choose from: NEPA reform, zoning, occupational licensing, DBCFT, even consumption taxes. Maybe the magnitude of manufacturing expansion would be large enough to be considered a success, maybe not, but it would doubtless have a positive impact. Not to mention a huge economic boom in construction and energy production as well. Supply side reforms are also gaining popularity on the left with Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book. Additionally, they do not risk destroying the global economy and upsetting our allies. There’s also a good political angle for Trump; the construction industry is a much better place to improve the prospects for blue collar male workers than manufacturing; it’s far bigger and less prone to automation. Turning manufacturing into an inefficient jobs program would harm the national security goals anyway.

Also, just as throwaway, Miran didn’t mention it, but immigration is key for manufacturing. SpaceX and Tesla are American manufacturing companies because Elon was able to come to the US; TSMC dominates semiconductors because Morris Chang decided not to stay in the US. The administration is certainly not even considering this strategy.

It’s also not clear we need to make a binary call as to whether we have or have not addressed the Triffen Dilemma. We need to hit some level of manufacturing base that would address national security or innovation concerns. Once a given national security or AI inflection points happen, there will likely be a huge amount of investment thrown into the problem. Existing assembly lines would need to be retooled anyway. The goal is to have enough expertise to quickly build what is needed. This is likely a spectrum. Moreover, the US is not starting from zero; there is plenty of advanced manufacturing. Regulatory and tax reform, coupled with Operation Warp Speed style incentives could do a lot before needing to gamble the entire global trading system.

The Fatal Conceit

Dean’s original tweet that inspired this post argued that classical liberals were in some sense naive and had not fully grasped the magnitude of the problem. Simply sticking to laissez-faire principles with a few keyhole solutions won’t cut it. But I think in fact it’s planners like Stephen Miran and everyone else further off the deep end in the Trump administration who have not grokked the free market critique. I argued earlier that we we weren’t following Miran’s plan. That’s true, but central planning will always fail. If they had understood Hayek, they’d know planners do not have the information available and cannot beat the market. If they had understood James Buchanan, they’d know they wouldn’t be able to pursue a singular goal of domestic manufacturing, but have to deal with a political coalition of interest groups all wanting different goals.

And the consequences really are dire. I don’t believe the markets have fully embraced how strongly the White House wants to keep these tariffs. Miran might want to keep them only as a negotiating tool, but virtually no one else does. And they may try to go much further, like remove the dollar as the reserve currency entirely. The impact on the dollar and treasury rates could be quite negative, with really catastrophic tail risks. The chaos we see isn’t just because the plan fell apart; it’s because the planners thought they could control the incentives of billions of actors in the market and come out unscathed. Their hubris doomed them, and perhaps will doom the US more broadly.